Cricket for a casual baseball fan

# 28 Jul 2017 by SeanMy father in law recently took me to my first cricket match: Australia vs England in the qualifying rounds of the Women’s Cricket World Cup. It was absolutely fantastic!

(This post is going to be pretty boring if you don’t like either baseball or cricket, FYI.)

Before I went, I was thinking of cricket as a weird hybrid of baseball and (10-pin) bowling: you have a batter, but rather than just hitting runs, their job is to stop the pitcher from knocking over some sticks set up just behind them. I can report that this is mostly inaccurate.

Well, that’s almost a true statement, except for the moments you get awesome plays like this, where they actually bowl the stumps:

(Sorry about the iframe like that… the video won’t embed.)

For the most part though, I’ve been trying to relate this to baseball, because having that background made understanding the new game a lot easier. Tracking what was similar, different, or morphed was what I did for most of the day. I’ve broken the differences/similarities into 3 categories: space, time, and strategies influenced by those. Also, seemingly shared vocabulary will throw you off.

Vocab to learn, and un-learn

- bowler, n. == pitcher

- to bowl, v. == to pitch

- pitch, n. == field

- batsperson (technically batsman… but), n. == batter

- run, n. == run, how you score. If you hit the ball to the inner boundary, you get 4 runs ‘for free’. If you hit it out of the park, you get 6. This game scores higher than baseball usually

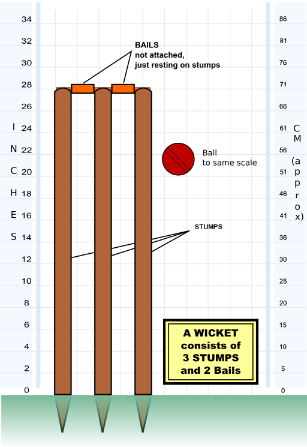

- wicket, n. == has 3 definitions, but the most important and concrete is that this is the structure of 3 up-right sticks (stumps) with two smaller sticks laid across the top (bales) (think Stonehenge). If a batsperson’s wicket is ‘taken’, or knowcked over, ze is out for the rest of the game. The bowler is trying to knock the bales off, and the batsperson is protecting them… hence the 10-pin bowling comparison. We’ll cover this in more depth later

- leg before wicket (lbw), n. == seriously this is a weird one. Closest thing you’ll get to a foul ball or a strike, but not at all the same. Important though, because cricket is not hockey and you can’t block with your body, despite the batsperson’s pads

- inning(s), n. == … we’ll cover this one under time. It gets weird for baseball folk

- over, n. == as innings, we’ll cover it in a sec

- wide, adj. == when a bowl goes too wide. Pretty much the same as a ball in baseball, except it counts whether the batter hits the ball or not. You get an extra bowl if the bowler goes wide, and the batter still gets to score runs of wide bowls if xe’s good and hit them. Xe is also awarded a run just cuz the bowler screwed up (again, in addition to anything else they scored)

- no ball, n. == kinda the same as a wide, but instead of the pitch going too far to the side, the penalty is for the bowler coming too far forward before releasing the ball. Same consequences (extra bowl, a free run, plus score for any made off the bowl anyways)

Space

The biggest differences between baseball and cricket spatially are you play in 360 degrees, the difference between a wicket and home plate, and that there are two batspeople running at any given time.

Because there are 360 degrees of playable field for the batter, there are no fouls. You can just as easily hit a 6-run play into the stands directly behind you as anywhere else in the field. It also makes fielding more interesting, because you have to spread your team more thinly, calculating not just whether the batsperson is going to hit close in or far out, but also to which sector of the field1.

Wickets, home plate, and the crease

The crease is the area where the batter stands, in front of xyr wicket. If you think about baseball’s homeplate as an abstracted wicket, it kinda makes sense: in baseball the batter is obliged to swing at any pitch that goes over the plate by the rules, else it’s a strike (and you’ve got three of those before you’re out for the moment); in cricket, the batsperson has to swing at any bowl that’s coming in because if xe doesn’t, the bowl will knock over the wicket and the batsperson is out (or it hits xyr leg and xe’s out on an Leg Before Wicket).

This is what a wicket looks like up close.

Two batters and no bases

That there are two batters in play is interesting: the configuration of pitchers mound and homeplate from baseball is instead set along a straight stretch in the center of the field (confusingly also called a wicket…), and there is a batsperson defending a wicket at each end. During an over (6 bowls/pitches, more on this in a minute) the bowler is bowling from one end of this, from behind one of the batspeople, and trying to take or bowl (over) the wicket of the batter on the far end. Batspeople score runs by both of them completing a run to the other side, changing the batsperson that the bowler is dealing with (though they can any number of runs, so it’s possible the bowler will face off against the same batsperson even after scoring).

Time

First up, there are 3 forms of the game: test cricket, 50-overs, and Twenty/20. The biggest difference between these three games is the length, which can have a pretty major impact on strategy (I imagine–only ever seen 50-overs). Test cricket is the insane game that lasts for a week. Twenty/20 is the new sexy game that’s over in a couple of hours. 50-overs matches are a full-day event, but just one day.

Innings

In cricket, an inning is a team’s turn at bat. Unlike baseball, there is no top or bottom of the inning; 2 at-bats would be represented by 2 innings. There are only ever 2 innings played on a day. This means that for 50 and Twenty/20, there are only 2 innings period. Test cricket will still have more innings, but you’re taking the week off to see the whole game. Once I started thinking about test cricket though, I realized that baseball is like test cricket compressed into a reasonable timeframe–alternating at-bats, with alternating opportunities to score. Baseball has the same structure, though the length of an at-bat (remember, this is the whole inning in cricket) is severely limited in baseball by the 3 outs rule. You need the equivalent of 10 outs in cricket to end the inning, and outs are a lot harder to come by.

50-overs and Twenty/20 cricket limit the length of play with a combination of having just 2 innings/at-bats, and by shortening their length.

Overs

Let’s not try to draw any parallels here. In cricket, the length of an inning is measured by the number of overs played (but can be ended early with enough batspeople out by having their wickets taken). The over is the sub-unit of the inning.

In Twenty/20 cricket, there are 20 overs in an inning. In 50-overs, 50. Test cricket is variable.

Overs are similar, on the surface, to a team’s at-bat in baseball, but: in cricket, an over is only ever 6 bowls2. In baseball, you could theoretically keep running through your batting order until you finally racked up 3 outs. Not so in cricket.

Also good to note that there is no such thing as a perfect game or a shut out in most of cricket. In time limited cricket, bowlers are only allowed to bowl so many overs, which means they can’t own an entire game like a pitcher can in baseball.

Time summary

This is kinda the thing that’s just different really… innings are not innings, and overs are not at-bats, though structurally for the game’s flow they’re similar. The structure of cricket’s flow is this:

during an inning:

- 1 team at bat (not both taking turns like baseball)

- can be ended early if the fielding team ‘takes’ 10 wickets (again, see below)

- 20 or 50 overs in the inning

- 6 bowls per over, not counting extra bowls required for mistakes

What’s the deal with wickets?

So there’s a big difference between baseball and cricket we haven’t addressed–what ‘out’ means.

In baseball, ‘out’ means that your time at bat or on base is over, but you will come back to the plate later on, possibly in the same inning. In cricket, ‘out’ means… out. Permanently. You will not bat again.

This is where the wickets (the stick-pile wickets) get really important–a batsperson is protecting xyr wicket. Once that wicket is ‘taken’, xe can no longer bat, and must be replaced by another player from the team. Because a team must field two batspeople at all times, and because there are 11 players on a team, this means that if the fielding team takes 10 wickets, the batting team can no field enough players and the inning ends3.

This is also the closest you’ll come to a perfect game in cricket–you could in theory take 10 wickets in the first 1 & 2/3 overs, immediately ending the inning without allowing a single run–but the perfect game, or even a shut-out, isn’t really a thing in the cricket world… yet. Wouldn’t be surprised if Twenty/20 started to pick it up.

You can also be caught out on the fly, so having your wicket taken isn’t the only way to get out.

Taking wickets

Two basic ways to take a wicket–the bowler knocks it over, or one of the fielders catches the ball and knocks the wicket apart before the approaching batsperson gets back into the crease (safe back on home plate). The fielder needs to have the ball in hand to do this, though xe can also throw the ball at the wicket to break it that way. Batspeople can also knock over their own wickets which is… embarrassing.

Leg before wicket

If the ball hits the batsman without first hitting the bat, but would have hit the wicket if the batsman was not there, and the ball does not pitch on the leg side of the wicket, the batsman will be out. However, if the ball strikes the batsman outside the line of the off-stump, and the batsman was attempting to play a stroke, he is not out.

– From Wikipedia’s Laws of Cricket entry

I’ll just leave that there. So confusing.

Other wickets

The word ‘wicket’ can also be used to refer to… OK. We’ve waited long enough.

THIS is what ‘wicket’ means to me dammit!

But seriously. In addition to the mini-Stonehenges that the batspeople protect (ok fine)

If you’re not thinking of this at some point during a game of cricket, you clearly haven’t lived.

OK, now for real. In addition to the mini-Stonehenges wickets that the batspeople protect, the term ‘wicket’ can also refer to:

- metaphorically, the ‘taking’ of a player’s wicket (knocking the bails off), which means to get a batsperson out

- the line of the field between the two physical wickets, where the bowling and runs happen

Strategy

A lot changes when you’re not alternating at bats regularly, and when out means out. Whereas in baseball batters aren’t obliged to swing at balls (pitches that are not over home plate for the English crowd), in cricket, you absolutely should swing at them if you can–you need to rack up runs, and there’s no such thing as a walk. Either you get the run or you don’t.

On the other hand, even if you hit the ball, you may not want to run. This was one of the things I found hardest–I saw a lot of plays where I was mentally shouting at the batspeople to run, because they had hit a grounder out between a few fielders. But they didn’t. Thing is, you have to be a lot more careful about leaving the safety of the crease (home plate) when out is a permanent thing.

This means that watching it can be occasionally frustrating, though there can be delicious amounts of tension that build up as a result.

All in all, cricket is kind of delightful–I’ve since used the analogy that cricket is to baseball as Star Trek chess is to chess. Extra dimensions, and takes a lot longer to play. But it is absolutely fantastic.

5/5 would get sunburnt all day again.

-

NB: field positions are defined generally off of the bats person’s body–leg-side, etc. ↩

-

These have to be legal bows, so wides and no balls don’t count against this limit, despite still being scorable. ↩

-

This is how the England women’s team won the World Cup on 2017-07-23: they took 10 wickets from India (good thing, because otherwise India was batting really well and probably would have beat England). ↩